In 2017 Vocal Rehabilitation Coach, Dane Chalfin, highlighted to BAPAM the benefit of singing rehabilitation coaches as part of the multidisciplinary team in specialist Voice Clinics which treat professional singers. At the time, there were a very few singing rehabilitation coaches working in this way in the NHS, and leading Laryngologists and Speech and Language Therapists working with BAPAM recognised the importance of the perspective of an appropriately trained and experienced vocal coach in the rehabilitation pathway of professional singers.

To support this concept, and with the approval of funders, BAPAM agreed a pilot project to collaborate with the NHS and fund Vocal Rehabilitation Coaches (VRCs) to work as part of the multidisciplinary team in four NHS voice clinics in order to demonstrate the value of this role.

In order for the pilot to take place, two important questions needed to be clarified:

- What competencies are required for a VRC to work in a clinical context?

- What is the optimal care pathway for professional voice users presenting with problems, and where does the VRC fit?

VRC Competencies

In 2017 Dane Chalfin carried out a survey of existing VRCs and allied clinicians to determine what, in their views, the competencies for the VRC role should be, and the first iteration of competencies were approved. As they were implemented, some further refinement has taken place and the current competencies are outlined below:

-

- Hold or have previously held a contract with an NHS specialist voice clinic including a job description. Verified by contract document. Where an informal but significant relationship with a voice clinic exists or has existed in the absence of a contract, a letter from the voice clinic may be accepted

- Have spent at least 6 years practising as a singing teacher/vocal coach within an educational institution or in private practice. Verified by contract document or evidence of proven track record

- Work under clinical supervision from both voice specialist laryngologist and speech therapist (as appropriate) as part of a clinic team with all clients. A psychosocial supervisor is desirable. If the applicant is working in private practice, letters from clinical supervisors confirming monthly sessions are required

- Undertake at least 20 hours of voice clinic observation per year. Verified by letter from voice clinic

- Have completed relevant anatomy/physiology that is delivered by experienced clinicians by written or practical examination

- Have completed endoscopic interpretation of singing physiology training, verified either with a written or practical examination, or by written confirmation from a suitably-qualified clinician that this standard has been attained.

- Have basic counselling awareness training, formal or in-house. Verified by attendance certificate or letter from voice clinic

- Have training to carry out palpation assessment, that is delivered by experienced clinicians by written or practical examination.

- Adhere to data protection standards when keeping client records

- Have current appropriate liability and indemnity insurance policies. Verified by documents

- Provide at least two references, one from a specialist voice clinic, one from a reputable professional performance-related company (ex: university or production company)

- Adhere to all BAPAM professional practice standards at all times

- Current DBS certificate

Care Pathway

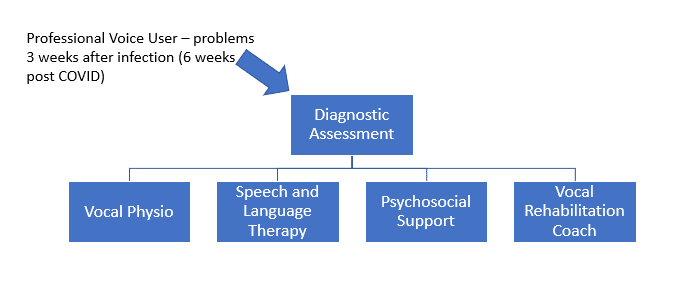

BAPAM developed a care pathway as guidance for the performing arts sector and for NHS GPs as follows:

For all performers with symptoms lasting more than 2-3 weeks, direct referral by the patient’s NHS GP to an NHS Specialist Voice Clinic (or privately if waiting time are long and if funders will support), so that diagnostic tests can rule out any pathology and a multidisciplinary assessment can be made and appropriate treatment recommended. Recommended management might include rehabilitation by a VRC working as part of the clinic team under clinical supervision.

Professional Standards and Educator’s Code of Practice

Professional Standards and Educator’s Code of Practice

As the project developed and VRCs became approved, it became clear that VRCs who had come from an education background were not always clear about the professional standards appropriate to working with patients in a clinical context, as opposed to working with students in an educational context. The professional training for education and clinical professions are, of course, very different. An Educator’s Code of Practice was developed to outline expected professional behaviours when working in a clinical context. All BAPAM VRCs are required to sign this: BAPAM Code of Practice for Educators

The Pilots

The process of giving an honorary contact to a VRC in the NHS is lengthy and in the last three years only one pilot has been completed, at Wythenshawe hospital in South Manchester. The COVID-19 pandemic also created a delay and even now, vocal health clinics are constrained because of social distancing. Carrie Garrett took on the role of VRC for this pilot.

Sue Jones, Consultant SLT at Wythenshawe wrote following the pilot “a very knowledgeable VRC is of value in the clinic.”

The Guys and St Thomas’ pilot is about to start and BAPAM’s funding of a VRC has enabled Tori Burnay, SLT, to set up a new parallel clinic for professional voice users. This is an unexpected and very positive outcome and highlights how a small contribution can support significant change in mainstream NHS services.

Meanwhile, Liverpool Broad Green and Newcastle Freeman hospitals have independently engaged a vocal coach to work with their professional voice clinics.

Clinicians working in Specialist Voice Clinics are very positive about having vocal coaches with the appropriate experience and training involved in the rehabilitation pathway of singers, and BAPAM will continue to approve BAPAM VRCs on our Directory of Practitioners so that healthcare and funding organisations can have confidence in the professionalism of these practitioners to carry out their role in rehabilitation.

What next for VRCs?

It seems that the time for a VRC pilot has passed. With hospital voice clinics starting to engage their own VRCs, the case has been successfully made. BAPAM will continue to support the development of the VRC role in NHS voice clinics. Instead of a pilot, we will be offering funding to emerging NHS Specialist Voice Clinics in the UK, particularly in areas where there is no NHS provision, to support local vocal coaches to gain the clinic experience to meet competencies and work as a VRC. We will continue to approve BAPAM VRCs on our Directory (although social distancing makes clinical experience hard to obtain in the current climate), and to recommend that charitable funding organisations continue to support this service as part of a rehabilitation pathway.

Clarifying the VRC role

There has been some confusion about the boundaries of this role. The generic term ‘Vocal Rehabilitation Coach’ is not protected by law, and anyone can call themselves a VRC: there are no legal requirements for any specific level of qualification, experience or mode of practice. This makes it difficult for a singer or funder to judge the competence of a practitioner when seeking support.

BAPAM’s Vocal Health Working Group, made up of laryngologists, SLT, Physiotherapist and VRC has worked to clarify the role of the ‘BAPAM VRC’ as a highly specialist singing coach who works with patients as part of a clinical team within a Voice Clinic and/or has a significant relationship with a Voice Clinic and receives referrals from a clinician. A BAPAM VRC will have met BAPAM competencies and agreed BAPAM’s Code of Practice and will have clinical supervision from a voice specialist Laryngologist and SLT and, ideally, a psychosocial professional. A BAPAM VRC can only provide rehabilitation:

- post-diagnosis and

- under clinician supervision

Additionally, they cannot provide laryngeal manipulations. These must be carried out by a trained clinical professional.

When working with a singer independently of a clinical team, for example in private teaching practice, the ‘BAPAM VRC’ should not use that title and should only be working as a vocal coach. If one of their students has a voice disorder more than 3 weeks post-infection, for example, they should arrange a diagnostic assessment in a Specialist Voice Clinic rather than providing direct care.

Long term development of the VRC role

BAPAM VRCs have reported the value of meeting together for peer support and BAPAM strongly suggests that UK VRCs work together to align themselves with, or apply to develop, a recognised professional body, such as those accredited by the Professional Standards Authority. This body would define and uphold standards, develop and accredit training, manage complaints and could also provide professional indemnity. BAPAM has held some of these functions on a voluntary, interim basis, and has sought to provide a structure for clinical oversight for those VRCs listed on the Directory of Practitioners, in order to benefit our patients.