Dr June Sheren is a Family Physician/General Practitioner from Singapore with special interest in performing arts health. She holds a Master’s degree in Performing Arts Medicine from University College London. She had the privilege of presenting her Master’s research on Performance-related Musculoskeletal Disorders in Orchestral Musicians at the Performing Arts Medicine Association (PAMA) Annual Symposium in 2023, New York City, supported by a generous grant from the National Arts Council, Singapore. She serves as medical advisor to the Singapore Symphony Orchestra and runs a musicians’ clinic for students of the Yong Siew Toh Conservatory of Music, National University of Singapore, providing a safe space for their physical and mental health needs. A member of PAMA, the Australian Society for Performing Arts Healthcare (ASPAH) and a founding member of the PAM interest group in Singapore, she is an advocate for health and wellbeing of performing artists. In her spare time, she plays the piano and cello.

“(I have seen) workers in whom certain morbid affections gradually arise from some particular posture of the limbs of unnatural movements of the body called for while they work. Such are the workers who all day stand or sit, stoop or are bent double… the harvest of diseases reaped by certain workers… (from) irregular motions in unnatural postures of the body.”

In his 1713 book De Morbis Artificum Diatriba (Diseases of Workers), Italian physician Bernadino Ramazzini first described the health problems of tradesmen including musicians, makers of lute strings, voice trainers and singers, thus creating the study of occupational medicine and conceptualizing musicians medicine all at once. Instrumental musicians experience health problems such as hearing issues, visual problems, performance anxiety, but none more frequently reported than musculoskeletal disorders. Muscle, joint and soft tissue problems occur when they are used to perform tasks in awkward positions or in frequent activities which over time can create pain and injury. A combination of over-exertion, repetitive motion and postural imbalance, along with overarching and unwavering attention to high precisional control, are the root causes of these injuries. The musician’s instrument is considered an extension of their mind and body. The widely accepted definition of performance-related musculoskeletal disorders (PRMD) by researchers Zaza and Farewell (1997) states that apart from pain, it also includes “…weakness, numbness, tingling, or other symptoms that interfere with your ability to play your instrument at the level you are accustomed to”. There is a difference between mild and transient aches and pains, and PRMD. PRMD can severely impact musicians’ personal and work life by restricting performance, leading to loss of opportunities and income, and even shortening one’s career.

Since the 1980s, research has suggested that PRMD is common in classical musicians at all levels, whether student or professional. In one of the earliest and largest studies on classical musicians by Fishbein et al, an alarming 82% of musicians reported ever having had a PRMD in their lifetime (Fishbein et al, 1987). A systematic review by Kok et al in 2016 found 86-89% of professional musicians and university music students had suffered PRMD in the previous 12 months. These are very high numbers – could PRMD really be so common? Are the majority of orchestral musicians really playing with pain?

Tracking down the Literature

The sheer diversity of musicians and their working background, together with the vast spectrum of musculoskeletal problems, means that research is also very diverse. Most studies on PRMD in classical musicians involve mixed groups of musicians – full-time professionals, freelance, part-time, students, educators all grouped together. Given their different levels of proficiency, hours of playing per day, ages, repertoire, and backgrounds, we could end up comparing apples with oranges. A fully employed violinist in a professional orchestra will be working and playing under very different conditions from a full-time educator or a conservatory student. Results from mixed studies must be interpreted with care.

I performed research – a literature review – looking at PRMD specifically in professional, full-time orchestral musicians, to gather as much information as there is out there on PRMD within professional orchestras. The search identified 21 papers which included some important studies involving major orchestras from the UK, Australia, Germany, Denmark, USA, Brazil, South Africa, Israel, among others.

Results

- Lifetime prevalence, meaning musicians experiencing PRMD at any time in their lives, ranged from 77.2% to 89.5% which is very high. Point prevalence which is PRMD at the time of the surveys, mostly ranged between 36.6% and 66% – meaning that at any point in time, one to two thirds of orchestral musicians were experiencing PRMD. 12-month prevalence referring to PRMD within 12 months prior to the survey was 45.5 to 88.6%. This meant that almost half to almost 90% of musicians experienced PRMD in their past year. These figures confirm how common PRMD is among orchestral musicians.

- The most common body parts affected by PRMD are the neck, shoulder, back and upper limb (upper arm to fingers), regardless of instrument played. There was not enough data to show differences between the right and left halves of the body.

- PMRD varied with instrument group. String instrumentalists as a whole most commonly reported PRMD, with upper string players most affected. Woodwind players reported more wrist/hand pain than others. Brass instrumentalists reported the lowest rates of PRMD in many studies, but they experienced a higher risk of problems in the jaw area and teeth. Among percussionists, an increased risk of problems in the hand and wrist areas was reported. A study found that musicians working with an elevated arm position (violinists, violists, flutists, trumpet and trombone players) had more neck- shoulder pain than others. Many authors found they could not make clear conclusions when instrumentalist numbers in their sample were small (such as brass, percussionists, harpists).

- Female musicians not only reported more PRMD than men, but they were also more likely to report pain in multiple body areas, suffered pain for longer periods and were more affected by the consequences.

- As to whether a musician’s age was a factor, the results were inconclusive. Some studies found more PRMD in older musicians, one found more PRMD in the middle category of age groups (35 to 45 years), and others found no association with age.

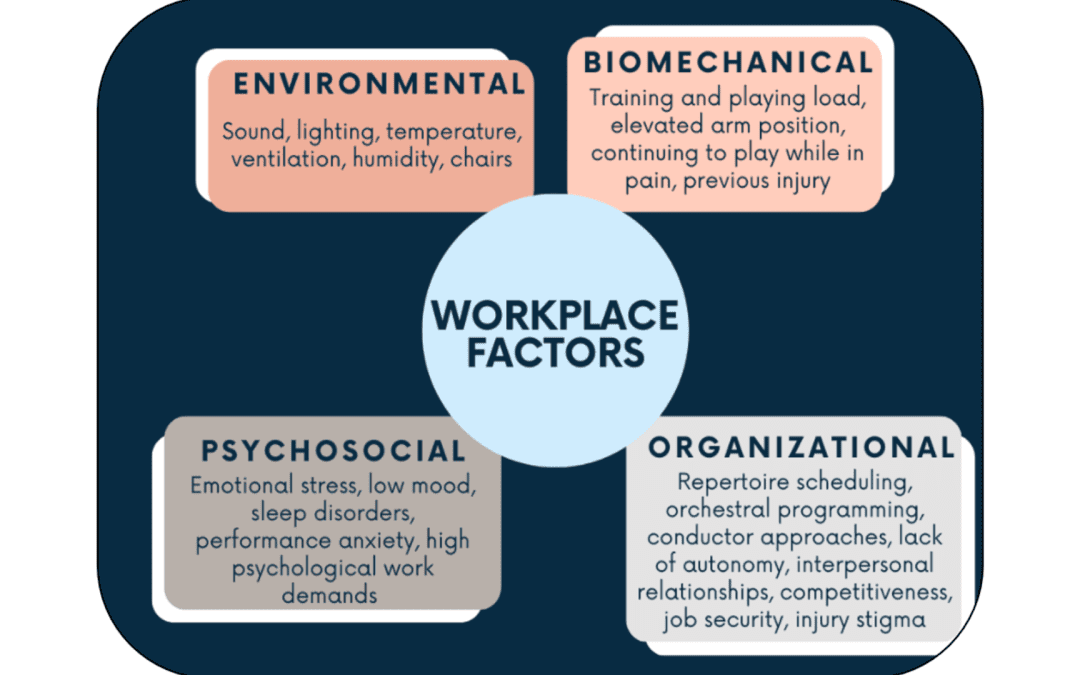

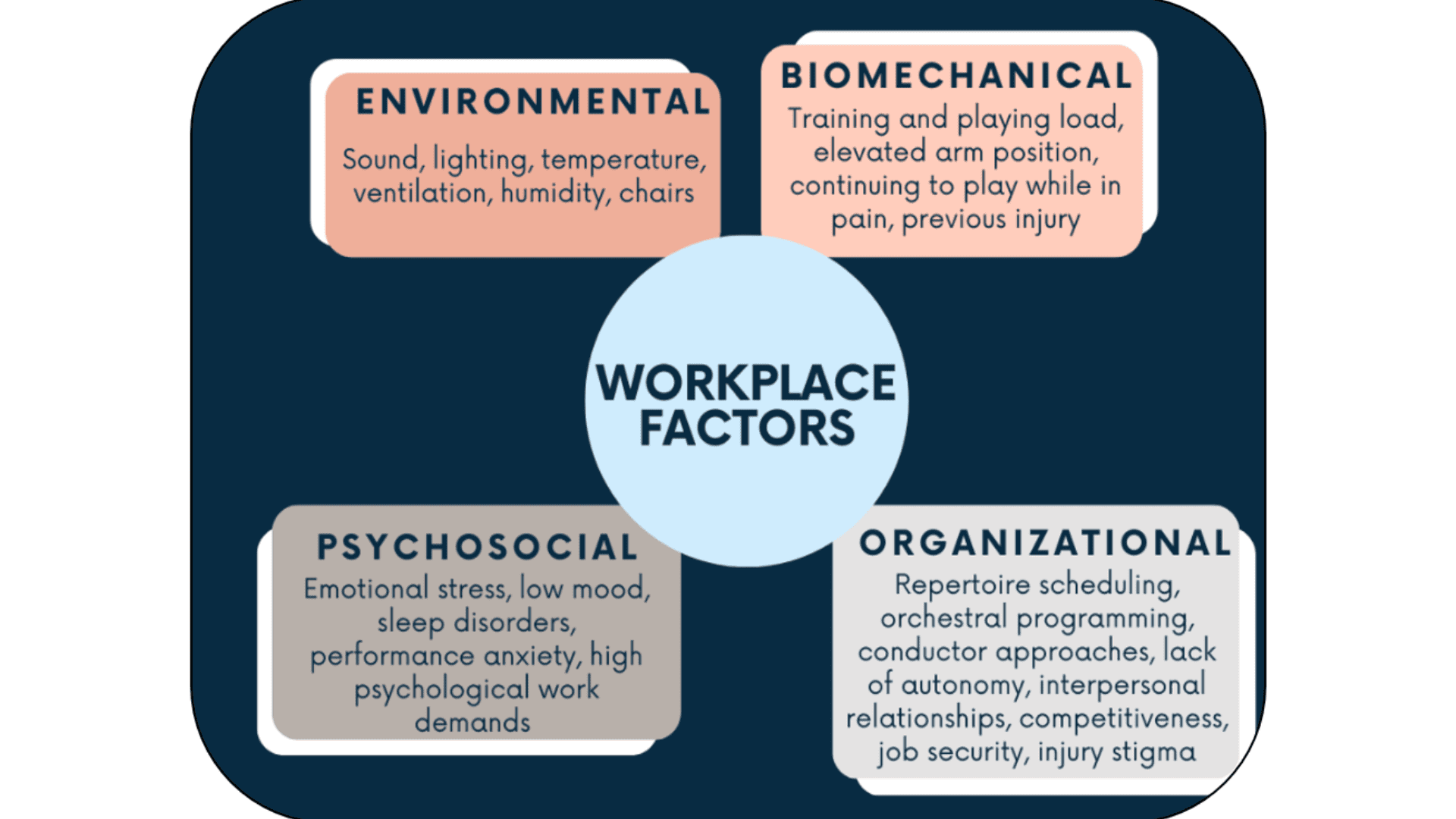

- On contributing factors, psychosocial factors like sleep disorders, emotional stress, high psychological work demands and performance anxiety were identified to be associated with PRMD. There are workplace factors to consider, such as the physical environment of rehearsal and performance venues – sound, space, lighting, temperature, ventilation, chairs, etc. Suboptimal conditions can place strain on the musician and increase the risk of fatigue and injury. Several studies reported training and playing load to be risk factors. Orchestra organizational structure may influence psychosocial factors contributing to PRMD. The causes of workplace psychosocial injury include high psychological work demands, low autonomy, problems with interpersonal relationships, low job satisfaction, and management styles that do not make employees feel supported. Additional layers include job and financial insecurity, negative attitudes to injury and injury stigmatization, competition, and fear of judgement – all of which contribute to job dissatisfaction and stress. Some authors observed health behaviours in orchestral musicians reflecting the culture of discipline and competitiveness inherent to the orchestral work environment.

Orchestra Workplace Factors

A few studies looked into the health behaviours of orchestra musicians including their choice of treatment method and perception of health. The range of treatments that musicians sought included doing nothing, stretching, massage, medicating, physiotherapy, and rarely, seeking medical treatment. Some studies found that despite high PRMD rates and severity, musicians denied having any health problems and instead reported themselves as being in good health. It has been suggested that musicians may perceive pain differently with the ability to separate PRMD from their general health, in addition to possessing unique coping strategies that allow them to play through pain.

What does this all mean?

PRMD is a very real issue and deserves to be better understood by all – not just musicians but also health professionals, music educators, and orchestra managers. Health education at the conservatory level is likely to play an important role in injury prevention (Matei et al., 2018). The female preponderance of PRMD reminds us that there are sex differences in health and illness, in pain perception and response. There is a need for more female-specific research to enhance healthcare for women (Borger et al, 2021). For example, physiological and hormonal upheavals in a woman’s life such as pregnancy and menopause impact musculoskeletal health. Evolving research in menopause has only recently led to updating of practice guidelines and improved treatment methods available to women.

Reviewing aspects of organizational structure and work culture will help identify some of the many workplace factors contributing to PRMD, and addressing these may be crucial to establishing a healthy work environment for all (Rickert et al., 2013). Finally, musicians’ unique health and pain perception underscores coping strategies; strategies that allow them to strive for perfection in artistry despite warning signals from the body (Nygaard Andersen et al.) Recognizing warning signs and acting on them, along with identifying trusted and qualified healthcare providers to work with, will be helpful in preventing PRMD at the individual level.

A better appreciation of the myriad of factors contributing to PRMD in orchestras allows fine-tuning of preventive strategies at every level, and ultimately serves to improve the health, well-being and longevity of musicians.

References

BORGER, T., NEL, E. J., KOK, L. M., MARINELLI, F. E. & WOLDENDORP, K. H. 2021. Risk Factors for Musculoskeletal Complaints in Female Musicians A Systematic Review and Exploration for Future Studies. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 36, 279-296.

FISHBEIN, M., MIDDLESTADT, S. E., OTTATI, V., STRAUS, S. & ELLIS, A. 1988. MEDICAL PROBLEMS AMONG ICSOM MUSICIANS – OVERVIEW OF A NATIONAL SURVEY (REPRINTED FROM SENZA-SORDINO, AUGUST 1987). Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 3, 1-8.

MATEI, R., BROAD, S., GOLDBART, J. & GINSBORG, J. 2018. Health Education for Musicians. Frontiers in Psychology, 9.

NYGAARD ANDERSEN, L., ROESSLER, K. K. & EICHBERG, H. Pain among professional orchestral musicians: a case study in body culture and health psychology. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 28, 124-30.

RICKERT, D. L., BARRETT, M. S. & ACKERMANN, B. J. 2013. Injury and the Orchestral Environment: Part I. The Role of Work Organisation and Psychosocial Factors in Injury Risk. Medical problems of performing artists, 28, 219-229.